Spearos – hunter fishers

By Katy Cummings

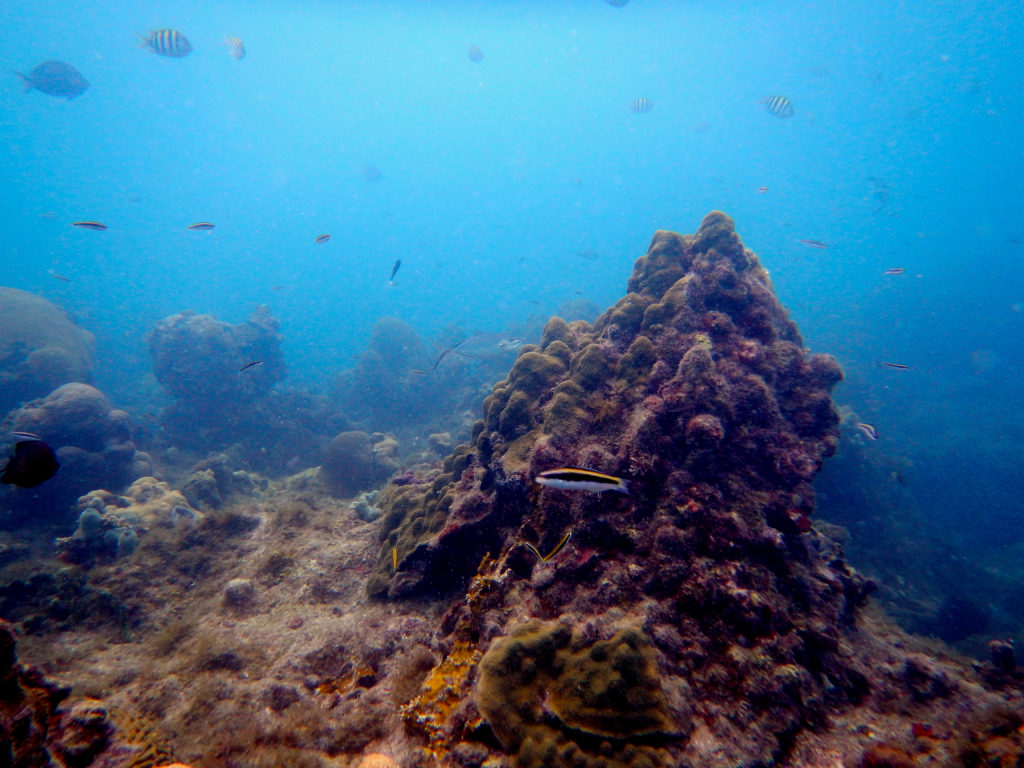

I hover over the reef in the clear, blue water of the Florida Keys. I’m looking for a large coral head to check under for grouper, ideally a mountainous star coral (Orbicella faveolata). I spot one– the large sentinels at the reef edge, a small mountain of coral the size of a Volkswagen van. Mountainous star coral make good hiding places for grouper, as the areas underneath are often full of cavities and holes from the growth pattern of the coral.

I relax my body, calm my breath, and dive down. As I get closer to the bottom the details of the reef come into view. I can see that half of this coral head is now dead, likely due to poor water quality, warming waters, and/or stony coral tissue loss disease, the most recent coral disease outbreak that is ravaging though Florida’s Coral Reef. Death by a thousand cuts. A lot of the dead area on the coral has been colonized by other organisms – sponges and octocorals, which are now the main creatures on the reefs here – that will make it harder for new corals to recruit here. –

I shine my light into the nearest hole under the coral and am greeted by a wall of fish. It’s the side of a large black grouper. The subtle beauty of the golden-brown spots on a dark background give it away. I figure out what way the fish’s head is, then back up and aim my spear at the fish, quartering towards the head. My shot is a little off – my spear comes out through the gill plate instead of the stone shot into the brain I was hoping for – and I need to take another breath to be able to pull the grouper out of the hole. I dispatch it on the surface with my knife and admire the glinting gold spots as I move back and forth in the sunlight.

Healthy coral is key to supporting healthy fish populations and black grouper such as this one. Countless animals depend on coral reefs for all or part of their lifecycle – corals are both an animal and a critically important habitat. Coral and the complicated structures they make as they grow their skeletons make lots of hidey-holes on the reef, provide protection from wave action and predators, and support the animals and plants the fish eat. You don’t need any special training to see the importance of reef structure with your own eyes– go to a dead reef, full of rubble and flattened by erosion, and compare it to a healthy reef you’ve seen. There will be far more fish on the healthy, rugose reef than there will be on the dead, flat reef. You don’t see anglers or spearos (a person that practices spearfishing) marking dead coral – we mark large coral heads, ledges, and complex reef habitat because that’s where the fish are.

It’s harder for people to understand the loss of our underwater ecosystems, or the importance of healthy habitat for wildlife populations in the same way we do with healthy forests for deer. Most of us can’t see it – we are floating on the surface above the habitat. That’s why spearos are so uniquely situated – as a hybrid of fishing and hunting, we are immersing ourselves in the habitat and are watching firsthand how our reefs are changing. Talk to people who dove on Florida’s Coral Reef decades ago– they will tell you about seeing lines of walking lobsters as far as the eye could see, about plentiful and large fish, dappled golden meadows of staghorn and elkhorn corals, with flitting butterflies of fish moving amongst the branches.

If you are a numbers person, I can tell you that our reefs have probably declined by about 60-90% depending on what area of the reef you are on in Florida. Some species have gone locally extinct on certain areas of the reef. Much of our reefs have been taken over by octocorals (like sea fans and sea plumes), which are pretty and purple and wave enticingly at you below the waves, but don’t provide the same habitat that stony corals do. The entire structure of the reef is changing, and with it goes the fish habitat.

When the coral dies, it’s skeleton will remain on the reef for some time, continuing to provide structure for fish. Eventually though, animals that bore into limestone will work to erode the skeletons, and ocean acidification is making this process easier by dissolving the dead reef. Our reefs are slowly flattening. Before the disease started in 2014, climate change, coastal development, pollution, and a myriad of causes worked together to make our waters unfriendly for corals. In this increasingly inhospitable environment, reefs lack the resiliency needed to fight back effectively.

Is all hope lost? Never. Scientists, reef managers, and the public are all taking action to combat the loss of our reefs. The “coral community” has come together like never before to address stony coral tissue loss disease. Researchers are working to answer important questions, including: What is causing the disease? How is it spread? How can we stop it? Intervention teams are treating corals with antibiotics, probiotics, and antivirals. Corals have even been rescued off the reef before the disease could reach them, moved to zoos and aquariums, and are being used in captive breeding programs as we speak. Their offspring will be returned to wild reefs when it is safe to do so.

What can spearfishers do? If you are traveling make sure to disinfect your dive gear with a diluted bleach solution. Don’t touch coral when laying in ambush or trying to get a fish out of a hole, and be mindful of your spear going through the fish and into living coral. And of course, anything you do to benefit the reef will boost coral health and help them to better recover from stressors like this in the future.

- Reduce your carbon footprint. Corals are sensitive and the predicted 1 degree Celsius of warming is already harming our reefs.

- Don’t excessively use fertilizer (better yet, plant a native plant yard!).

- Live near the ocean and still on septic? Remember, s*** runs downhill…. right into our oceans and onto the reefs. Look into getting hooked up to a sewer system.

- Use reef-friendly sunscreen – most mineral-based sunscreens are reef-friendly; most other sunscreens are not.

- Reduce your use of single-use plastics and pick up marine debris.

- Don’t touch coral, and especially be mindful of living coral when laying on the reef to ambush fish or when reaching into holes.

- Don’t let your boat or anchor touch coral either – familiarize yourself with nautical charts and the area you will be fishing in, heed navigational markers, and only anchor in sand (or better yet, use mooring buoys if available).